Tallahassee Democrat Tallahassee, Florida Wednesday, August 29, 1962 - Page 4

Chess and the Cold War 29 Aug 1962, Wed Tallahassee Democrat (Tallahassee, Florida) Newspapers.com

Chess and the Cold War 29 Aug 1962, Wed Tallahassee Democrat (Tallahassee, Florida) Newspapers.com

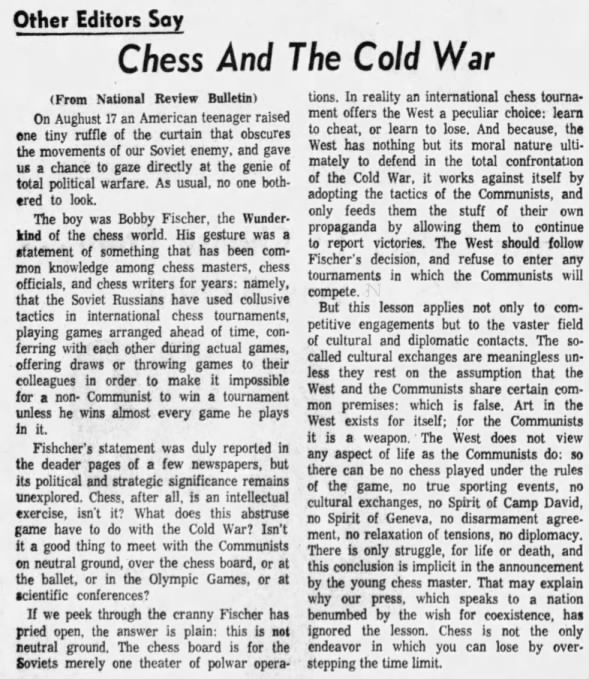

Chess and the Cold War

On August 17 an American teenager raised one tiny ruffle of the curtain that obscures the movements of our Soviet enemy, and gave us a chance to gaze directly at the genie of total political warfare. As usual, no one bothered to look.

The boy was Bobby Fischer, the Wunderkind of the chess world. His gesture was a statement of something that has been common knowledge among chess masters, chess officials, and chess writers for years: namely, that the Soviet Russians have used collusive tactics in international chess tournaments, playing games arranged ahead of time, conferring with each other during actual games, offering draws or throwing games to their colleagues in order to make it impossible for a non-Communist to win a tournament unless he wins almost every game he plays in it.

Fischer's statement was duly reported in the deader pages of a few newspapers, but its political and strategic significance remains unexplored. Chess, after all, is an intellectual exercise, isn't it? What does this abstruse game have to do with the Cold War? Isn't it a good thing to meet with the Communists on neutral ground, over the chess board, or at the ballet, or in the Olympic Games, or at scientific conferences?

If we peek through the cranny Fischer has pried open, the answer is plain: this is not neutral ground. The chess board is for the Soviets merely one theater of cold war operations. In reality an international chess tournament offers the West a peculiar choice: learn to cheat, or learn to lose. And because, the West has nothing but its moral nature ultimately to defend in the total confrontation of the Cold War, it works against itself by adopting the tactics of the Communists, and only feeds them the stuff of their own propaganda by allowing them to continue to report victories. The West should follow Fischer's decision, and refuse to enter any tournaments in which the Communists will compete.

But this lesson applies not only to competitive engagements but to the vaster field of cultural and diplomatic contacts. The socalled cultural exchanges are meaningless unless they rest on the assumption that the West and the Communists share certain common premises: which is false. Art in the West exists for itself; for the Communists it is a weapon. The West does not view any aspect of life as the Communists do: so there can be no chess played under the rules of the game, no true sporting events, no cultural exchanges, no Spirit of Camp David, no Spirit of Geneva, no disarmament agreement, no relaxation of tensions, no diplomacy. There is only struggle, for life or death, and this conclusion is implicit in the announcement by the young chess master. That may explain why our press, which speaks to a nation benumbed by the wish for coexistence, has ignored the lesson. Chess is not the only endeavor in which you can lose by overstepping the time limit.